The Nightmare of Childhood

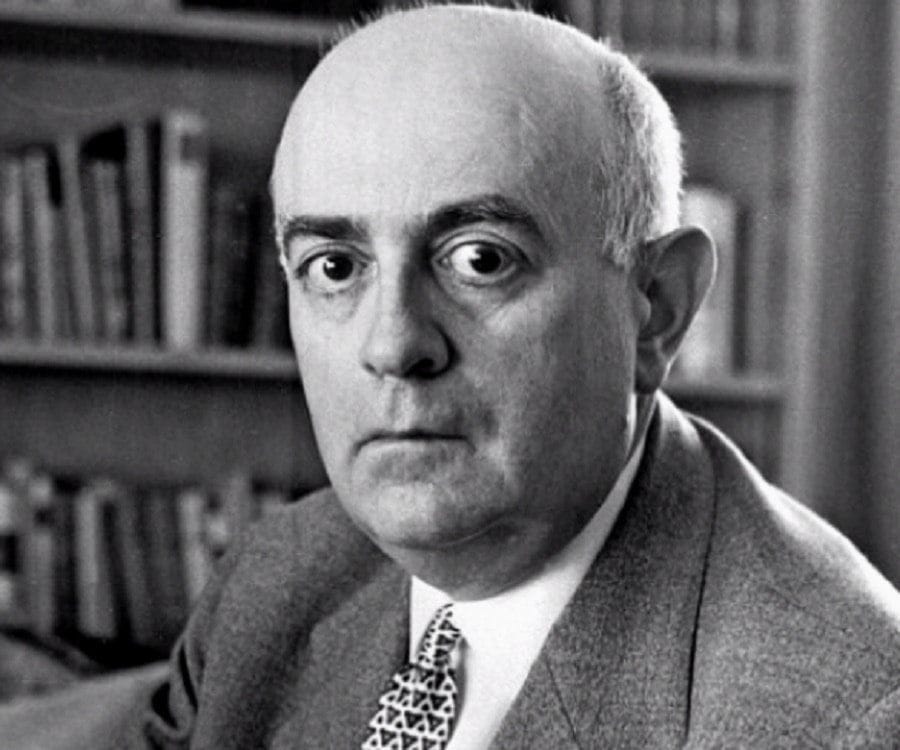

Theodor Adorno tells us why getting stuffed in a locker is fascism

One of the most penetrating aspects of Theodore Kaczynski’s analysis of industrial society and its failings—the so-called “Unabomber Manifesto” or, to give it its proper name, “Industrial Society and Its Future”—is his discussion of the psychology of leftism. In particular, Kaczynski focuses on two aspects of the leftist personality as an ideal type (an abstraction drawn from many cases): “oversocialisation” and “feelings of inferiority.”

Kaczynski felt a discussion of leftist psychology was necessary, because he believed leftism was “one of the most widespread manifestations of the craziness of our world.” By “leftists,” Kaczysnki means “socialists, collectivists, ‘politically correct’ types, feminists, gay and disability activists, animal rights activists and the like.’

“Oversocialisation,” one of the two defining traits of the modern leftist, consists of a deep sense of identification with the social and moral code, to the extent that “the attempt to think, feel and act morally imposes a severe burden on [the leftist].” In order to avoid a feeling of guilt, the leftist must continually “deceive themselves about their own motives and find moral explanations for feelings and actions that in reality have a non-moral origin.”

“The oversocialised person,” says Kaczynski, “is kept on a psychological leash and spends his life running on rails that society has laid down for him. In many oversocialised people this results in a sense of constraint and powerlessness that can be a severe hardship.”

The most oversocialised leftists tend to be the middle-class leftists and university intellectuals. Oversocialisation leads leftists into a bizarre parody of rebellion in which, to satisfy their guilty conscience, they claim to be fighting against society’s conventions and codes, when in fact they are actually upholding them.

The second of the two defining traits is feelings of inferiority, which seems rather self-explanatory. Leftists are consumed by feelings that they are inferior: “low self-esteem, feelings of powerlessness, depressive tendencies, defeatism, guilt, self-hatred, etc.” In large part, as with oversocialisation, this explains why the most ardent leftists—“those who are most sensitive about ‘politically correct’ terminology”—are drawn from the white middle classes and the universities. Leftists overidentify with groups that are perceived as “weak,” “defeated,” “repellent,” or “otherwise inferior,” and conversely “tend to hate anything that has an image of being strong, good and successful.” Those things include America, Western civilisation, white men and rationality.

The leftist, as a result, is “anti-individualist” and “pro-collective”; the leftist celebrates, even exalts, what is sordid and debased and irrational; he engages in the most masochistic forms of protest and display, laying down in front of cars in the street, “provok[ing] the police or racists to abuse [him]”; and whatever feelings of strength he has comes solely from his membership of the collective and not from any individual powers of his own.

Kaczynski provides a devastating indictment of leftist false consciousness, which is worth quoting in full.

Leftists may claim that their activism is motivated by compassion or by moral principles, and moral principle does play a role for the leftist of the oversocialized type. But compassion and moral principle cannot be the main motives for leftist activism. Hostility is too prominent a component of leftist behavior; so is the drive for power. Moreover, much leftist behavior is not rationally calculated to be of benefit to the people whom the leftists claim to be trying to help. For example, if one believes that affirmative action is good for black people, does it make sense to demand affirmative action in hostile or dogmatic terms? Obviously it would be more productive to take a diplomatic and conciliatory approach that would make at least verbal and symbolic concessions to white people who think that affirmative action discriminates against them. But leftist activists do not take such an approach because it would not satisfy their emotional needs. Helping black people is not their real goal. Instead, race problems serve as an excuse for them to express their own hostility and frustrated need for power. In doing so they actually harm black people, because the activists’ hostile attitude toward the white majority tends to intensify race hatred.

*

The true, rather than the professed, motivations of leftists are a fixture of discussion for the online right today, three decades after Ted Kaczynski wrote his “manifesto.” The inferiority and “titanic resentment” that drive leftists are discussed at length in Bronze Age Mindset, a foundational text of the “dissident right”; and feature regularly in the general cut and thrust of day-to-day Tweeting and trolling.

I was thinking about the subject specifically a couple of days ago after I fished out my copy of Theodor Adorno’s Minima Moralia: Reflections from Damaged Life from a big box in the attic. I hadn’t gone up there to look for it—I actually brought down a lot of books—but when I got the box into the dining room and started rummaging through it, the book jumped out at me, probably because it’s absolutely the last thing I’d read today, given the choice. I can’t have looked at Minima Moralia in at least a decade, maybe more, since I was at Cambridge reading social anthropology.

I used to have this habit of leaving little sticky markers on pages where something grabbed my attention, so I followed the markers I’d left all those years ago. For the most part, as I read, it was unclear to me why I’d marked the aphorisms at all. What significance they’d had to me was lost with the passage of time and the shrivelling of whatever small parts of my brain might—might—have been receptive to the work of a Frankfurt School Marxist once upon a time.

But then I came to a very striking aphorism and its significance was obvious to me now at least. Aphorism 123: “The Bad Comrade.” Here’s how it begins.

In a real sense, I ought to be able to deduce fascism from the memories of my childhood. As a conqueror dispatches envoys to the remotest provinces, Fascism had sent its advance guard there long before it marched in: my schoolfellows. If the bourgeois class has from time immemorial nurtured the dream of a brutal national community, of oppression of all by all; children already equipped with Christian-names like Horst and Jürgen and surnames like Bergenroth, Bojunga and Eckhardt enacted the dream before the adults were historically ripe for its realisation.

Basically, Adorno is saying that school is a microcosm of fascism. The unruly, rough and ready young boys—the jocks—terrorising the nerdy wimps: that’s a prelude to fascism in adulthood. And, in Adorno’s own life, it was a prelude to actual fascism: to the rise of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi party. The aphorism was written in 1935, after he had fled Germany for the US.

Adorno is describing the indignities of being a nerd and getting stuffed in a locker. But he’s investing it with a kind of cosmic significance.