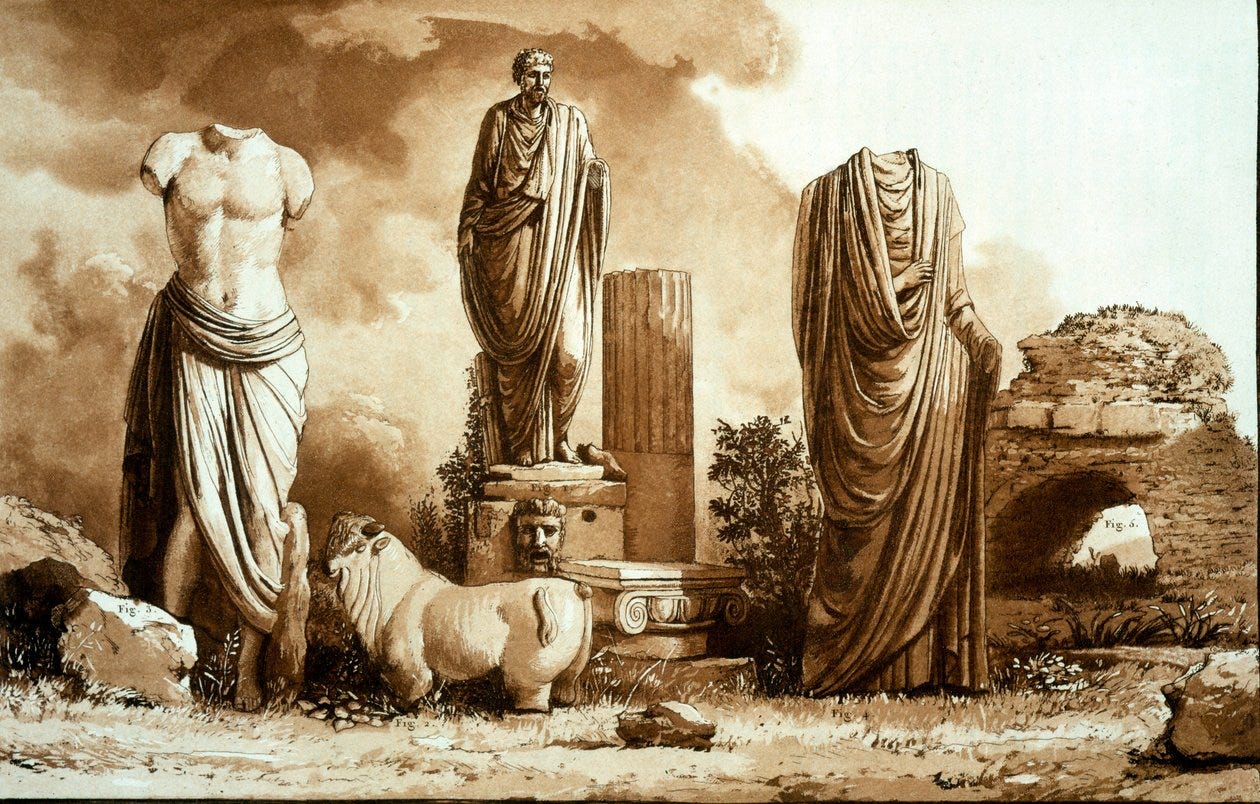

The Headless Tyrant

An essay on the nature of modern tyranny

This essay originally appeared in Issue Three of The Islander magazine.

One tradition in modern political philosophy sees the main role of the sovereign—the ruler—as being the guarantor of peace and social order within his realm. This role is part of a “social contract” between ruler and ruled.

The ruled give up certain of their freedoms to the ruler, and in return they get safety, stability and justice.

On the English side of this tradition, the most famous example is, of course, Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan, published in 1651. As Hobbes put it, the agreement between sovereign and subjects brings to an end “the war of all against all”: the state of nature in which man exists by default, a place where life is “nasty, brutish and short” and any man has the power to kill any other should he choose to do so.

Sovereignty of this kind rests on a monopoly over violence. This monopoly over violence has been integral to modern theories of the state. Here’s Max Weber’s famous definition of the state, from his 1919 lecture “Politics as a Vocation”:

Today, however, we have to say that a state is a human community that (successfully) claims the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory. Note that “territory” is one of the characteristics of the state. Specifically, at the present time, the right to use physical force is ascribed to other institutions or to individuals only to the extent to which the state permits it. The state is considered the sole source of the “right” to use violence. Hence, “politics” for us means striving to share power or striving to influence the distribution of power, either among states or among groups within a state.

But there’s an alternative tradition, with far deeper roots than the early modern period, that sees the sovereign in precisely the opposite terms. Instead of guaranteeing order, the sovereign guarantees disorder. He does this to strengthen his own rule and ensure that his people are never powerful enough to challenge him.

This is the tradition of political tyranny first described in detail by Aristotle, in the Politics, especially in Book V, Chapter 11. Although Aristotle wrote the Politics 2,300 years ago, he provides, to my mind, the most accurate description of the methods and purposes of governments across the West today. Not one of those governments is a formal monarchy gone bad, and yet they are tyrannies just as surely as if they were ruled by Periander of Corinth or Orthagoras or any of the other ancient tyrants Aristotle mentions by name.

Aristotle describes tyranny as the reverse or “counterpart” of properly constituted monarchy. Tyranny is “just that arbitrary power of an individual who is responsible to no one, and governs all alike, whether equals or betters, with a view to its own advantage; not to that of its subjects, and therefore against their will.” Aristotle provides a long description of the methods of tyrants, which is worth quoting at length. Aristotle phrases it as advice—the tyrant should…—but the Politics wasn’t intended as a how-to guide for budding tyrants.

Says Aristotle,

“the tyrant should lop off those who are too high; he must put to death men of spirit; he must not allow common meals, clubs, education and the like; he must be upon his guard against anything which is likely to inspire either courage or confidence among his subjects; he must prohibit schools or other meetings for discussion, and he must take every means to prevent people from knowing one another (for mutual acquaintance begets mutual confidence).”

There are a variety of ways tyrants maintain their power: preventing free association; surveillance; keeping an extensive network of informers; sowing quarrels among citizens; impoverishing them, especially with high taxes; making wars to distract them. Aristotle also notes that tyrants prefer bad men and “like foreigners better than citizens… for the one are enemies, but the others enter into no rivalry with him.”

Aristotle does give some direct advice to tyrants. He tells them they should be more kinglike if they want to hold on to their rule, which means at least feigning genuine concern for their subjects and putting a leash on their worst impulses.

But like I said, Aristotle wasn’t writing a handbook.

You could easily be forgiven for thinking, though, that Western governments had been reading Aristotle on tyranny as a guide. Back in the 1990s, the American political commentator Sam Francis gave a name to the modern democratic inflection of ancient tyranny, in an American context. He called it “anarcho-tyranny.”

Personally, I might quibble with the addition of “anarcho-,” since it implies that anarchy is an addition to the tyrant’s bag of tricks, when in fact, as Aristotle makes clear, it was there in Ancient Greece too—sowing quarrels, starting wars, etc. But that’s just a quibble.

Francis considered anarcho-tyranny the dominant form of government in the US, whether of the left or right. As he saw it, the state allows certain forms of lawlessness to flourish, encourages them even, in order to secure its control over the tax-producing middle classes, who are terrified into submission. Aristotle doesn’t actually state that tyrants encourage crime among the citizenry, but that could be inferred from what he does say, and the methods Francis describes are certainly familiar from the Politics. Francis also adds a whole slew of updated and new techniques that are used to enforce anarcho-tyranny:

…exorbitant taxation, bureaucratic regulation; the invasion of privacy, and the engineering of social institutions, such as the family and local schools; the imposition of thought control through “sensitivity training” and multiculturalist curricula; “hate crime” laws; gun-control laws that punish or disarm otherwise law-abiding citizens but have no impact on violent criminals who get guns illegally; and a vast labyrinth of other measures.

Examples of anarcho-tyranny at work in the US today are not hard to find. Perhaps the biggest and best recent example would be the Summer of Floyd and the mostly peaceful protests of 2020. Remember: these took place during the COVID-19 pandemic, when ordinary people were supposed to be confined to their homes and practising “social distancing” from one another. But because the riots served a useful political purpose for the left and elements of the American regime—making racism the most important national issue during an election year when a “racist” president was running for re-election—they were allowed to take place across the length and breadth of the US for months, at a cost of at least $2 billion to the insurance industry. The true cost was far greater, of course, and must take into account the enormous transfer of wealth, the largest in American history, that the riots helped grease the skids for, as small middle-class businesses were run to the wall first by the pandemic restrictions and then by the looting and disorder, while mega-corporations like Amazon hoovered up their business and posted record profits. The riots, with their focus on reparations for America’s black population, also prepared the ground for future race-based policies of redistribution from the dwindling, but still hugely productive, white majority.

We saw this pattern repeated across the Western world in 2020, including in the UK, where protesters against the pandemic social restrictions were treated harshly, with jackboot and truncheon, while BLM protesters were allowed to march in large numbers and even in paramilitary uniform, totally unimpeded, through London, and also received touching gestures of support from police and politicians.

Another way to consider the hold of anarcho-tyranny over Western societies is to consider its mirror-image: a society where crime is actively discouraged and punished harshly. El Salvador, under its current president Nayib Bukele, is such a place. Since declaring a state of emergency two years ago, El Salvador has gone from being the world’s most dangerous country—with a murder rate on a par with an active warzone—to the safest country in the Western Hemisphere.

Its gang problem has simply disappeared. And how? Bukele arrested all the gang members, easily identifiable from their tattoos, and threw them in prison, where they remain. He constructed a special new prison called CECOT (“Centro de Confinamiento del Terrorismo” or “the Terrorism Confinement Centre”) to house thousands of them. This mega prison covers 410 acres and has a maximum capacity of 40,000, making it one of the largest in the world. At present, CECOT is at about a third of its full capacity.

Off the back of his crackdown on El Salvador’s gangs, Bukele recently won a landslide re-election, with 87% of the vote. There’s every indication that the election was free and fair—certainly freer and fairer than the last election in the US. Bukele is the most popular president in Latin America, by an enormous margin. The people love him, because it’s possible now to do normal things like go out after dark and not get raped, robbed or killed. After decades, foreign investment is starting to flow back into the country.

Bukele has shown that, contrary to what we’re told in the West, crime is not simply a “fact of life” like the weather—an inconvenience that nobody can really do anything about. No: The existence of endemic crime in a society rests on a choice, and given the choice, most people would gladly get rid of it. But in Western societies, the choice is made for the citizenry regardless of their opinions on the matter.

The Western response to Bukele—from governments, NGOs and the press—has been extremely revealing. The denunciations and screeching have focused exclusively on the human rights of the gang members themselves and not on the rights of ordinary Salvadoreans to live peaceful lives free from the constant threat of violence and death. This says everything you need to know about Western governments’ real concerns back home too. It also reminds us of the role that NGOs and the press play in bolstering and justifying anarcho-tyranny.