Ozempic: Some Notes and Two Studies

More on some emerging side effects of weight-loss drugs

As you probably know already, I have my reservations about weight-loss drugs like Ozempic. You probably do too.

In broad terms, my objections can be grouped into two classes: moral on the one hand, and iatrogenic—meaning to do with medical harm—on the other. Looked at a little closer, however, the moral objection collapses into the iatrogenic. Everything I dislike about Ozempic and GLP-1-receptor-agonist drugs can be classed as iatrogenic, as a form of medical harm.

The outwardly moral objection is the easiest to understand. It’s also, perhaps, the easiest to dismiss. Simply put, I don’t like unearned virtue. I think if people can’t motivate themselves to be slim and healthy, they shouldn’t be slim and healthy—or slim, at least.

I’ve always been a bit of a moral absolutist, and as somebody who is motivated and does care and work hard, I don’t like the idea of a pill to replace hard work, or for people to be able to lie about how they got in shape.

My stance has started to soften somewhat in recent months. I’m not sure the majority of people will ever be able to motivate themselves to make the right choices.

Once upon a time, people simply didn’t have the ability to make the kind of wrong choices people make today. You just couldn’t live and eat like a typical 600lb American landwhale. And so, absent some kind of earth-shattering change to the way food is produced and sold and the way the average person lives, I don’t think there can be meaningful change. In a world of unlimited easy, satisfying bad choices, most people just can’t be expected to do the right thing, even when they know they’re destroying their own health.

A significant component of obesity is genetic too, to add to the handicap.

Having said all of that, and it is a fairly substantial modification of my earlier views on Ozempic, I still think we shouldn’t let go of this moral objection. I think it serves, most importantly, as a break on the most serious iatrogenic harms. If we totally decouple weight management from individual responsibility, we’re in big trouble. Because then weight management becomes somebody else’s responsibility—and that means government and corporations.

This is the more weighty of the iatrogenic objections I have, and I’ll return to it in a moment.

The less weighty objection, although still a matter of life and death potentially, centres on drug side effects in the more obvious, traditional, sense. Things like chronic bowel obstruction, gastroparesis, “diarrhea forever,” mood changes and suicidal ideation. We’ve seen a whole host of these already, and in fact it feels like barely a week passes without some new one like blindness or even “Ozempic vagina,” whatever that is.

Truth is, we don’t full understand the safety profile of these drugs, and their side effects are obviously being played down in the rush to make mountains of cash. Most people don’t know that GLP-1 drugs reliably induce thyroid tumours in rodents, for example. Well, they do. There’s been no long-term safety testing of these drugs in humans, and so we’ll all act surprised—the drug companies certainly will—when people start getting thyroid tumours too.

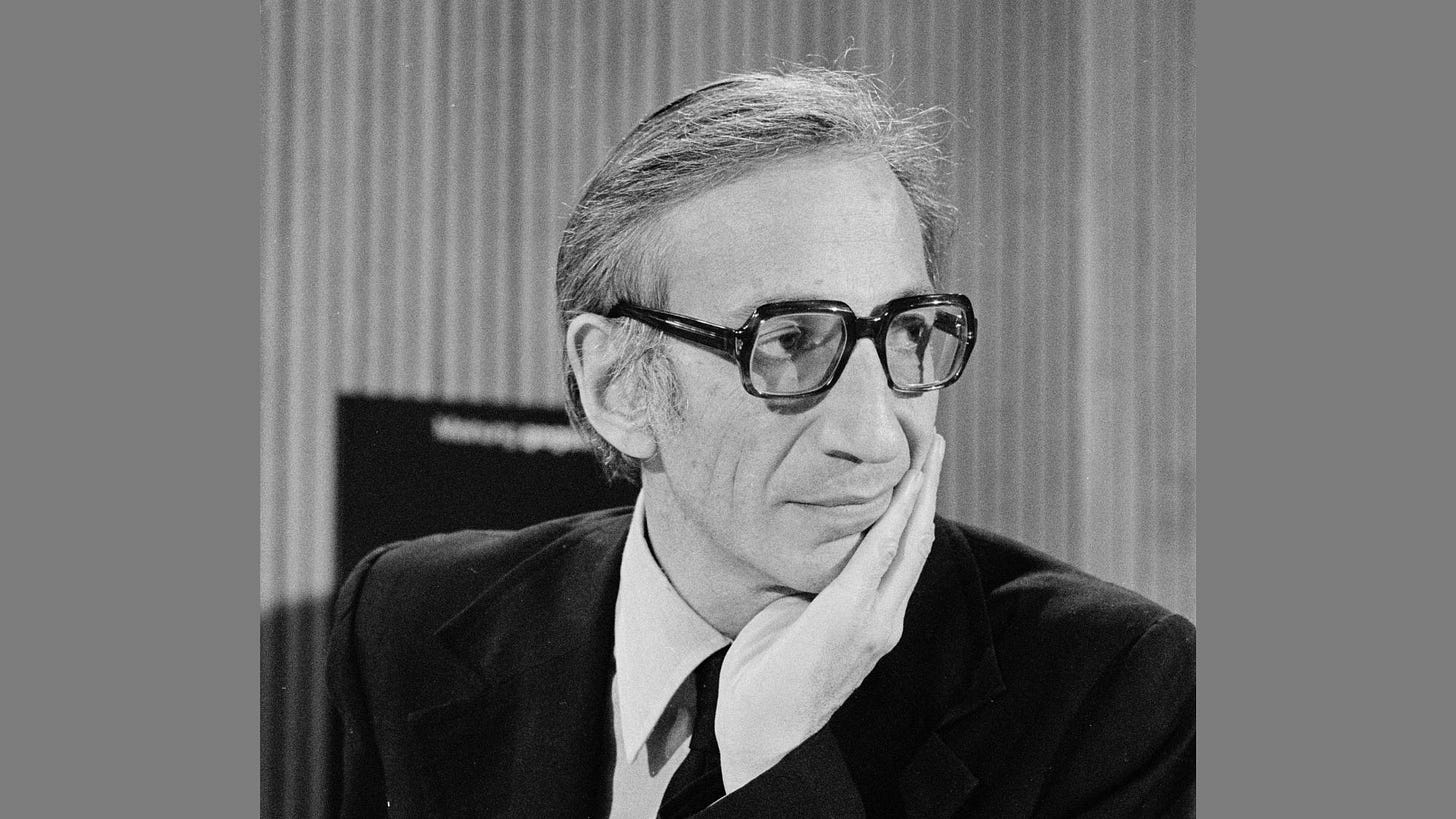

The weighter objection concerns what the philosopher Ivan Illich, in his book Medical Nemesis, calls “social” or “cultural” iatrogenesis. This is what creeping medicalisation does to society and, in particular, how it deprives people of scope for meaningful action on their own terms, robbing them of the freedom to choose how to live and how to approach the eternal problem of pain and suffering.

We’ve already surrendered enormous amounts of control to the medical industry. The medical industry now regulates our moods to a degree that was once only possible to imagine within the pages of a science-fiction novel—and a dystopian one, at that. In Scotland, a full quarter of the adult population, more than a million people—is now on anti-depressants. A similar proportion also take at least one other of the most common classes of psychotropic drugs, like anti-anxiety medication, so-called Z-drugs, benzodiazepines, etc.

The pandemic response, a true medical tyranny, would never have been possible without the enormous medicalisation of society: without a medically led crusade against pain that has given corporations, scientists and government the most wide-ranging powers over our health and lives. I can’t think of a better example of social or cultural iatrogenesis; although I suppose things could still get worse, and the temporary state of exception could become permanent.

This has been a very roundabout way—much longer than I’d intended—of introducing a couple of new studies that fall firmly in the “less weighty” category of iatrogenic objections to GLP-1 drugs. Both studies point to new side effects. You’re unlikely to have encountered these studies, unless of course you’ve been keeping an eagle eye on my Twitter feed.

STUDY ONE: Ozempic reduces muscle strength even when muscles stay the same size

There’s been a lot of talk about the effects of GLP-1 drugs on body composition, especially whether the dramatic weight loss reported is really as beneficial as we’re led to believe.

Drug manufacturers like Novo Nordisk, the maker of Ozempic, have tended to report total weight loss in their clinical data, without a breakdown of fat vs lean tissue.

What if a significant proportion of the weight lost from these drugs is actually lean tissue, including muscle? What if the proportion is greater than would otherwise be lost by following a traditional programme of calorie restriction and exercise?

Studies have already suggested that Ozempic causes excessive lean-tissue loss. This new study suggests the problems may be even deeper.

Even when muscle mass isn’t lost, Ozempic nevertheless appears to have negative effects on muscle function, making muscles weaker. The exact mechanism by which this happens isn’t known yet, so further research is required.

It’s worth noting that this was a rodent study, so the results have not been replicated in humans yet.

STUDY TWO: Weight loss drugs mobilise large quantities of toxic chemicals stored in fat, with unknown effects